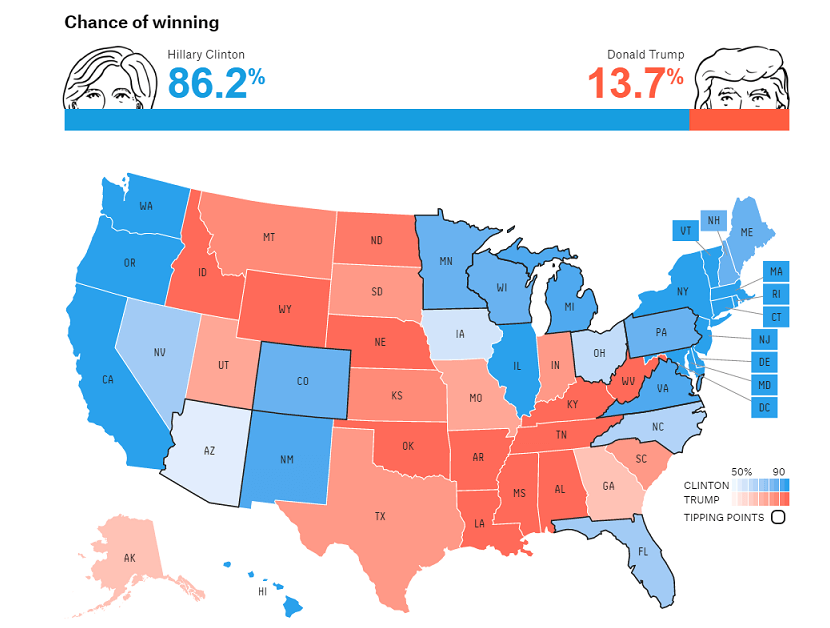

(Photo: Screengrab/http://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/2016-election-forecast/) FiveThirtyEight prediction map for presidential election, accessed Thursday, October 20, 2016.

Information technology and data science have been among the great disrupters of business paradigms in recent decades. The day when they play a similar role in political elections may have already arrived.

Since election day there has been no shortage of theories advanced to explain Donald Trump’s surprise victory in the US presidential race. Explanations have focused on the importance of rural white voters and their antipathy toward the “establishment” and elites, a weak economic recovery coupled with increasing income inequality, lower voter turnout among Democratic voters in key swing states, a nativist political movement sweeping the globe, racism, and misogyny.

I suspect all of these factors played a role. But so did the Trump campaign’s decision to forego the traditional tsunami of spending on broadcast ads targeted at demographic groups in favor of narrowcast digital ads.

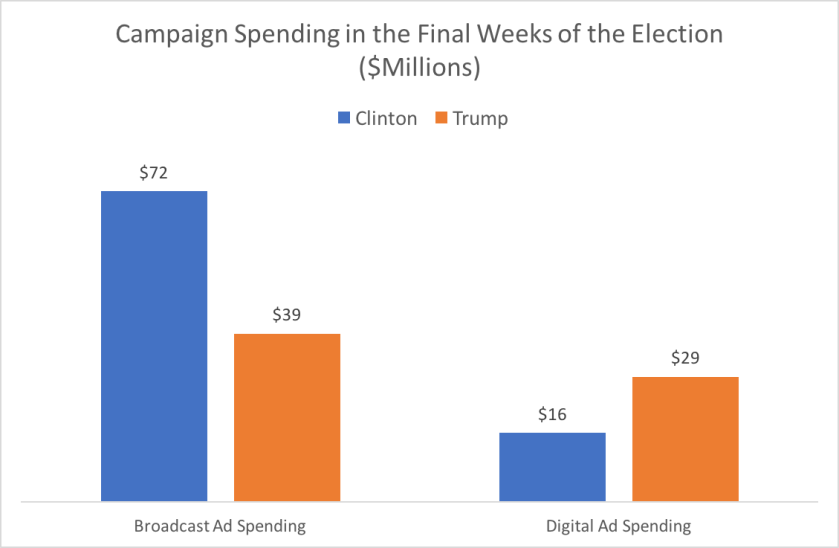

The Trump campaign spent far less than the Clinton campaign did on TV and radio ads, while leaning more heavily on digital marketing. The chart below shows figures reported by Fortune for each campaign’s ad spending in the final weeks of the election (starting Oct. 20). A similar spending gap on traditional broadcast channels had been seen throughout the campaign, with Clinton spending roughly three times as much as Trump on TV and radio spots prior to Oct. 20.

As Bloomberg BusinessWeek reported in October, the Trump campaign’s digital messaging strategy leaned heavily on Facebook. In particular, it made use of so-called “dark posts” – nonpublic Facebook posts that could only be seen by those the campaign wanted to see them. These were particularly useful in targeted voter suppression campaigns (e.g., placing a video of Clinton’s controversial 1996 comment that some African-American males were “super-predators” into the feeds of potential African-American voters).

More sophisticated data modeling was reportedly deployed on behalf of the Trump campaign by Cambridge Analytica, a firm that touts psychographic profiling as its competitive edge.

The idea of psychographic profiling or psychographic segmentation – targeting groups with similar interests, personality traits, and needs – has been around since the 1960s. But until recently efforts at developing robust, useable segmentations based on psychographic factors were hampered by the difficulty of identifying which segment an individual belonged to. Market researchers could survey a sample of consumers and use their responses to create segments that were likely to respond in predictable ways to specific product features or marketing messages. They could size the segments by using the principles of statistical sampling to project the survey results to the population as a whole. But they could not confidently assign a given consumer (or voter) to a segment for targeting unless he or she happened to be a member of the survey sample.

The nearly universal adoption of social media and smartphones – and the resulting ability to purchase hundreds of terabytes of individually identifiable data on consumers’ preferences (i.e., “likes”) has solved that problem. If you can identify useful psychographic segments inside that ocean of likes, posts, and retweets you can target precisely tailored messages to the right people. It’s as if 68% of the adult US population was part of your survey sample.

And yes, you can identify useful psychographic segments inside that ocean of social media data. One of the most widely accepted models of personality measurement, the Five Factor Model, postulates that much of a person’s behavior can be understood in terms of their levels of openness to new ideas and experiences, conscientiousness (impulse control and ability to stay on task), extraversion (engagement with the outside world), agreeableness (communal orientation, often with an optimistic view of human nature), and neuroticism (tendency to experience negative emotions). Recent research out of Stanford has shown that regression models based on Facebook likes can predict people’s scores on these five personality traits better than their Facebook friends can and almost as well as other studies found their spouses can.

This is essentially what Cambridge Analytica claims to have done for the Trump campaign – use Facebook likes, linked to other third-party data sources on party affiliation and voter registration, to target specific undecided or “persuadable” voters with messages that would resonate with their personality profile. If true, this represents a pivotal moment in the ability of data science to influence political outcomes.

Moreover, it represents a serious challenge to the Democratic party in its bid to regroup and mount a counteroffensive against Republican dominance in Washington. Steve Bannon is on Cambridge Analytica’s board, and Robert and Rebekah Mercer – among Trump’s largest financial contributors – are key investors in the firm. And, prior to the Trump campaign, Cambridge Analytica’s biggest success story was its role in the victory of Great Britain’s pro-Brexit forces.

In other words, Cambridge Analytica is a successful firm at the forefront of applying data science to political campaigns which is largely owned and directed by the “alt-right.”

If the Democrats hope to remain competitive they need to bring their political advertising and targeting strategies into the 21st Century. That means making a serious investment in digital marketing and cutting-edge data analytics, and weaning themselves off their reliance on television and radio advertising.

As a follow-up, here’s Facebook’s marketing team touting their role in getting Senator Pat Toomey (R-PA) re-elected. https://www.facebook.com/business/success/toomey-for-senate

LikeLike